Bones, Myths, and Broken Universes: An Interview with Michael Le Baron

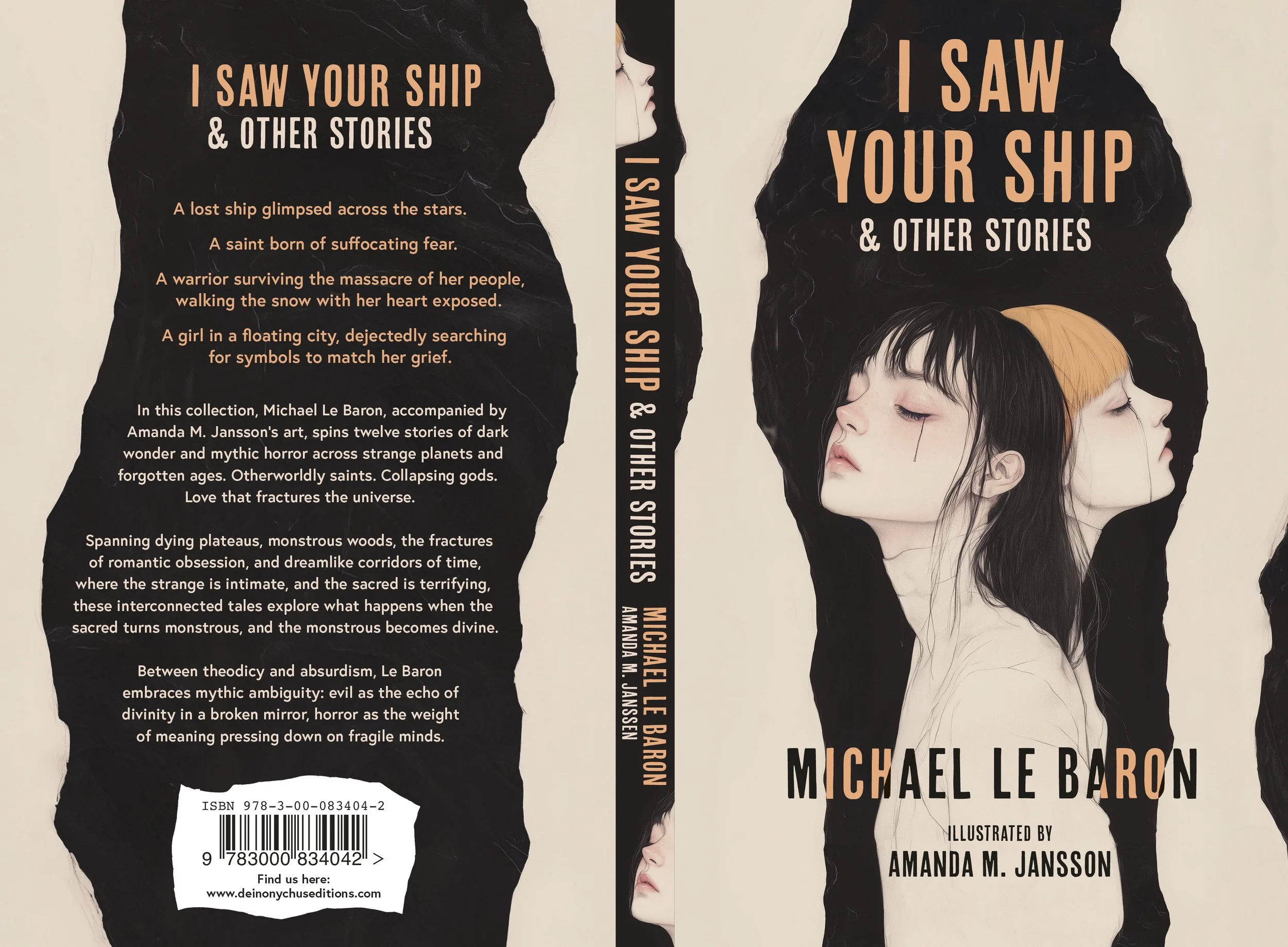

Michael Le Baron writes like someone standing in two worlds at once — one foot in the brutal vastness of the cosmos, the other in the fragile, trembling heart of lived experience. In this conversation, he opens the door to the emotional engines behind I Saw Your Ship: the ghosts that follow him, the violence and tenderness braided through his imagination, the myths he channels rather than invents. What emerges is a portrait of a writer who treats storytelling as both haunting and devotion — a way of giving shape to longing, suffering, wonder, and the strange, aching grace of simply being alive.

Your collection, “I Saw Your Ship,” weaves together myth, horror, and cosmic wonder. When you write, do you see yourself as a mythmaker, a dreamer, or?

I think all humans, and probably even a lot of non-humans are mythmakers and dreamers. I tend to believe that it's a fundamental characteristic of life- like breathing or the will to life, death or whatever you might call it. In terms of how I see myself, it's as someone who has feelings, stories, images, characters in his head, and I want to get them out there and make them live in some way. When I write, I have to be in a really particular inward place, where I can just focus on a particular frequency- entering that other world. It's a very emotional activity for me, usually with music involved, and emphasis on activity. It's taking the myths and the dreams and turning them into something coherent and entertaining and structural. I liken it to the notion of a spirit medium who would sort of avail themselves to the invisible and channel that into something their community can understand. That's what all artists do, and I think that extends beyond writing, illustration, dance, filmmaking etc into athletics, coding, science. There's a relation there to the Japanese concept of dō ("The Way” same idea as "Tao”) which implies a transformation of motion and practice into transcendence through intentional engagement. The best kind of art has that intentional engagement, rather than something impassive, impersonal, and mass-produced. Most of all, I want to tell a good story and entertain, but I also want there to be something true in there that comes from a very authentic emotional place.

There’s a recurring tension in your fiction between violence and tenderness. How do you balance brutality with beauty in your worldbuilding?

Growing up in the US and Canada- violence is a major part of the mythos- in the form of the brutality of the frontier- the frontier being a liminal proving ground where survival, resilience, and toughness are what form your identity. That comes in different flavours in Worcester Massachusetts; San Antonio, Texas; San Francisco or Sacramento, California; Vancouver Island or the Canadian Rockies, but there's a common foundation- not just human violence but the beauty and violence of the natural world. My family is intimately connected with all that. I used to go camping a lot and never went without my rifle. It's just something you grow with. So I don't really set out with the aim to put those in there- I think it sort of comes from the mythic fabric that I inherited in North America. When writing a story I have a situation, character, place, or feeling that I start with. Sometimes it's a dream I've had. Two of the stories are directly based on dreams I've had. So I start with this idea or texture, and I just let it live. I let it come to life, let it breathe. Then it sort of tells its own story. So as is the case in life, it's not always going to be that great or pleasant. There's so much suffering in life, so much violence, fear- there are horrific things that you just scarcely can't believe. And yet there's tenderness, love, and beauty too. But it doesn't negate how truly awful some things are. Those things are incomprehensible. Like the problem of evil. And we have to face them somehow. What do we make of evil? Philosophers and theologians have struggled with that problem for ages. In my stories, I don't try to answer it, but evil or pain or suffering, whatever you call it- just seems to be a component of what it means to be alive. To feel oneself as a finite being in a seemingly infinite universe. That's horrific. That's at the root of all cosmic horror, but I think also great literature, and great stories. I love the apophatic theological tradition because it doesn't try to explain reality, but rather immerses the beholder, the subject into the darkness; those things that don't make sense. Then, theologians like Karl Rahner and Bernard Lonergan have spoken of grace as component that comes to us as firmly rooted in the depths of human experience, of the living subject, and having the ordinary, the painful, the mundane become sources of that ontological opening where we really feel that relation to the universe that gave voice to us, to where we'll return. We're all in that same place, when I look at my children or my loved ones I know they are too, and there's a deep sadness and tenderness in that. The best stories let brutality and tenderness exist in the same emotional pulse- not in a contradictory way, but in a way that affirms what it means to be alive. I think a lot of anime and manga like Naruto, Inuyasha, Made In Abyss, and of course Evangelion do this beautifully, and authors like Shusako Endo, Clarice Lispector, and Inio Asano. I was asked once what kind of genre the book was and I called it "love horror,” a little allusion to the Finnish band HIM characterised as "love metal.” Like Ville Valo I'm interested in where that cry of anguish that comes from finding the place where the roots of horror/metal and love intertwine. So then for this book it's that the conversation with the indifference of cosmic horror doesn't end there. Ok the universe is cold and indifferent and existence is a cruel joke. So then what? We're here and we have to do something with that, and others are around us and they have to do something with that. And usually some kind of love is what's fueling us- whether it's love of another or love of ourselves, love of being alive…And really I think that most good stories are that: horrible things happen and there's a call to adventure, and then characters who we become invested in engage with it in some way with a burning love, whether that love is rewarding or ultimately destructive, there is a tenderness and compassion to be found there. I think brutality and tenderness both come from very honest and authentic places. When I was younger I used to box and play ice hockey. There was something in the struggle and the fight that was so true and honest to me. Pure physicality and this is at the heart of things like performance, dance, and somatic therapy. That’s why I love certain sports because they carry a truth and honesty about life and mortality. And that honesty can be as true as the gentlest touch. It’s the truest expression of the core of being alive. Amanda's art perfectly evokes all this, which is why I was so happy and honoured to work with her.

Many of your stories touch on characters who are haunted — by memory, grief, or something supernatural. Where does your inspiration for their inner ghosts come from?

I've lived in some very haunted places: strange creaking old houses in New England, dark woods in Canada, and of course the charismatic and chimeric Berlin. I think that ghosts are really everywhere- like Arthur Machen said, we bring a bit of ourselves to places, but a place brings something of itself to us too. I was always a really scared kid. I grew up in the 80s and kids’ movies were absolutely horrifying: Watership Down, Dark Crystal, Something Wicked This Way Comes. And that horror became familiar, beloved, and ultimately for my sister and I it became a way of coping. We got really into checking out scary places and feeling that fear and laughing about it. To this day we just love scary and disturbing things. And as life builds up you just keep getting haunted by new things: deaths, goodbyes, regrets, shame. Then there are the ghosts that are passed down- ghosts of violence, like in my dad's North American family, and ghosts of diaspora and identity erasure like in my mom's family's generational migrations from Central Asia to West Asia to North Africa and ultimately the US. We talk about genetic memory which are patterns or behaviours that get passed down, a hauntology of family trees. There are environmental ghosts- I remember fishing in Santa Barbara once and the fish I caught were all full of oil, I had to just throw them away. Nearby I worked at a seal sanctuary and I would often see lost babies calling for their moms- a lot would ultimately die- it would happen when they would get separated too early and the mother wouldn't recognise them. The seal colony was right next to the dock for an oil company. Yet those two coexisted- the oil workers actually watched out for the seals and protected them- they sponsored the sanctuary. At the same time, we were taking samples of ocean water to track warming, right next to the bodies of dead baby seals. That wasn't this oil company's fault- it was just cycles, things coming and going… returning. That's all sort of the essence of Derrida's idea of "hauntology” - with both the past and present disrupting linear time because they're always reemerging and influencing us. I'm fascinated by abandoned homes or things- that were once cherished and loved, and then left behind. Those really capture the essence of that haunting for me. There are ghosts in all of us: former lives, former relationships, memories that are gone and only ours like Roy Baty's “...tears in the rain.” For me there are ghosts of shame, ghosts of my parents when I was a kid, ghosts of woods or streets I used to walk in, ghosts of a marriage that didn't work, ghosts of a painful summer, ghosts of the babies my sons used to be… You know, I see ghosts everywhere- absolutely everywhere, and they haunt me. My dad, who was a doctor, did too I think- he wrote a book called Ordinary Deaths, that is very much a ghost story as life's review journey about coming to terms with death after witnessing it in its various forms. It's a phenomenal book. And my dad was, I assume, going to meet these ghosts of patients, a lot of them kids. For me too, writing lets me really get acquainted with those ghosts- my own and also seeing how they could exist in others, in different forms. Since happen to be writing fiction and fictional characters in imaginary worlds, it's a kind of performance, inhabiting these characters and discovering their ghosts. I did a lot of theatre when I was younger- both directing and acting. When I was acting, naturally there was a bit of myself in there- whichever character I was playing. I played a lot of villains and it was fun because it allowed me to really explore that darker part of myself that was haunting me. When I was directing, I would cast people based on how they embodied a specific character. Not just their delivery or their personality, but their very physicality- which I think plays into personality. One of the best castings I ever did was a guy who had never acted in his life and was an absolute, consummate "jock”type. And he just rocked that role because he physically embodied that character, who was a sort of ethical thug named Mike in Wait Until Dark. This kid, he was Mike- he was carrying everything that Mike was, maybe in a less tested or damaged form, but it was there- in his movements, in his body. Like he was haunting this character Mike with his own experiences, and vice-versa. So it's really about starting with characters that interest me and playing their roles on the page. And I have to tap into some really honest and painful things that I recognize. Performance still shapes how I think about characters, whether it is film, theatre, dance, opera, or even certain forms of cosplay. For instance, there’s a cosplayer who goes by the name endomarfa whose work I've come across, and she has an exceptional ability to inhabit characters in tender, unsettling, and remarkably honest ways. I don’t have that kind of visual or physical artistry, so for me the performance has to remain on the page. So I try to evoke similar textures and layers even in a brief glimpse of a character, in the way that performers like her manage to do through embodiment. In my stories, Cloutier, for example, is missing his family, and I know what that is like as a dad separated from the mom of my kids; I know what it is like to miss them. Or Turner thinking about his brother in the tunnel reminds me of my sister or my sons and their relationship with each other.- I know what it's like to miss them. Or Turner thinking about his brother in the tunnel- I think about my sister or my sons and their relationship with each other. For Hannah and Laurent, it's so toxic, but I think we've all been in relationships that weren't the best, or had tough or difficult moments. Hopefully not to the extent as Hannah, but the ghosts of those memories can live and continue- they can take lives of their own and become really monstrous. Heron, in I Saw Your Ship is really haunted by her past actions, by things she's done and also by a lot of probably unresolved issues that we never really explore, and ultimately haunted by this love for Lia. In Longing Toward You, Tantri is almost totally a literal ghost, except she's still, impossibly, alive. In Iye-Dewa Tseng is dealing with the ghosts of his family and dead daughter, but also exploitation, class dynamics, blue collar life, and the vastness of space. The Unicorn in What Happened? Is a haunting that is recalling hunger, reckless consumption, and extinction- a more environmental ghost story similar to the idea of the wendigo haunting the American West as an allegory for Manifest Destiny in the film “Ravenous.” And then there are the ghosts of place like in "With Your Face” or “Solanine.” My favourite ghost of a place story of all time is Picnic at Hanging Rock, where the girls become part of a haunting that seems to intersect with cyclical time, other universes, and their own personal struggles and hidden traumas. The most interesting, powerful, and monstrous ghosts I think get created by these cataclysms of varying size in a slice of time that shatter their location (whether human or landscape), and then they stay and haunt. Ultimately, we haunt ourselves the most, just as places haunt themselves.

The ship in the title, “I Saw Your Ship,” feels like a metaphor for longing. What does that ship represent to you?

It definitely connects to longing. So here's how I actually got the name “I Saw Your Ship.” It was 2006 and I was studying at the University of Salzburg- it was a special study in international law. Before I went to Austria, I was staying with my cousin in Paris. I was trying to nap in her apartment on this really hot day- there was a heatwave going on- and she had this set up where the breeze would come in along with the fan, so it wasn't too bad. I've always been really into MMOs and I'd recently dipped into EVE Online- not in an intense way, but more casual. I was listening to the soundtrack while closing my eyes and I heard this song that was beautiful and sad in this simple way that twisted my heart in the gentlest way. I opened my eyes and saw the name: “I Saw Your Ship” by Jon Hallur. It was just achingly beautiful and it evoked something really strong in me. This idea is to state you saw their ship. It means you're looking out at someone you care about, it doesn't have to be romantic, but you are really wanting anything of them that you can get. It's this intense and dangerous kind of love, not in a stalker way, but in the way that it could just absolutely break you. It's sort of infantile- like a child longing for that safety, that closeness. You're happy about it because you can see this ship that they're in, but it hurts because you're not with them.

So ultimately when I started writing this story about Heron and Lia, that thought came back to me again- how heartbreaking that title was. As the story evolved, the title started to carry multiple meanings where "ship” can have the fandom meaning of seeing the Heron/Lia ship, as if they were part of some other work and we shipped their impossible love. Then there's the "see” part which is connected to this concept, this being the Watcher which appears at the beginning and the end of the collection. It has agency, but is ultimately an expression of the universe, indicating that the universe is seeing them, just as we are seeing them. But what is a ship ultimately- a contained, comfortable (I always thought the best ships would seem very cosy and comfortable), a vessel taking you through the horrifying and brutal cold of space and infinity. I mean our planet is a ship in a way, our bodies are ships, our relationships are ships. The ship is temporal- it's all we have.

How do you think about time in your stories? Is it cyclical, broken, or simply meaningless?

Well I've played around in these stories with I guess what could be called multiversal ideas, which is interesting because that never much appealed to me in fiction. I mean, I've even put books down when I discerned that multiverses were part of the story. I preferred contained worlds- smaller, more intimate settings. I guess in the end what I didn't like was this idea of multiverses and time travel in the literal or "scifi engineering” sense, which was still linear and simplistic to me. Rather what got me intrigued with playing with universes connecting and time as cyclical was my love of myth which tends to do that a lot. I remember hearing an interview with the author Sherman Alexie where he talks about cyclical time in indigenous narrative, with characters showing up in different ways in his stories as if they are jumping through time. But they're not Marty McFly in the Delorean (no offense to franchise- it's so loveable), they're echoes that transcend space and time, which is a lot how we process the past and the future, and situate ourselves in terms of existence. This connects really well to Carlo Rovelli, whose work I love, and the notion that reality is something so far beyond our understanding- we can't fathom our relationship to space and time. I mentioned the apophatic tradition before, and the "cloud of unknowing.” One of my favourite portions of the Bible is when God is busting out these questions to Job and they're all like koan riddles. I allude to one of them in Heron's thoughts: does the rain have a father? The very idea of infinity, of the universe, is absolutely beyond our ability to fully comprehend. I'm no mathematician but at an intuitive level I believe that. In the end, there's a kind of hope that we're not some brief blip and then the lights shut off forever, but that our existence… no matter maybe because I think that's an elusive thing… but echoes and actually substantially is not one bit distinct from everything else in this universe or any other. One of my favourite books is a graphic novel called Girl on the Shore by Inio Asano- where two characters experience what they're going through in terms of fragments, memories, and in the end, they seem like they're kids again. Their story becomes these overlapping layers of memory, perception, and possibility that make a very contained and intimate story feel mythic. Time, if we accept Rovelli's thesis, isn't linear but is more like an emergent property made up of multiple state interactions. So in Girl on the Shore, or Picnic at Hanging Rock, or the stories in my collection- time isn't broken, meaningless, or even cyclical, but rather relational to all of these geographies of stars, mountains, forests, and hearts.

If someone asked you to describe your collection in three words — but you couldn’t use “dark,” “cosmic,” or “mythic” — what words would you choose?

Grief-stricken, cracked, vulnerable, and alive.

Where do you hope a reader is when they finish your book? What do you want them to feel or carry?

Hopefully the reader has enjoyed the stories and felt these worlds and characters come alive through the writing and through Amanda's art. That's primary for me. Next, I hope that they do carry that sense that while the universe is terrifying in its indifference, coldness, and violence, and being alive feels like a cruel accident, there is a grace that permeates all of it that can be found in the stillness, beauty, and gentle sadness of everyday life, and even beyond in the most brutal circumstances. So there's a lot of devastation in the stories, but I hope that that lingering thread of hope connects with the reader. We don't know quite what it is, but I think the greatest stories in literature have felt that it's there. Some of my greatest influences have been the Strugatsky Brothers, Joyce Carol Oates, Clarice Lispector, Inio Asano, Ursula K. LeGuin, and Clarke Ashton Smith. Their ability to write beautiful words, compelling stories, and evoke those themes are phenomenal. There are more, but I think these authors did that very well. I think that the intertwining of pain and love, futility and purpose, horror and resilience, are at the heart of our great stories, the heart of the questions the world's religions aim to tackle, and at the heart of everything we do, and everyone we love.

https://deinonychuseditions.com

https://www.amazon.de/Saw-Your-Ship-Other-Stories/dp/3000834044